Yahdon Israel, Cerebral Sartorial

Importer of the literary, exporter of the swag. This is how Yahdon Israel - a 26-year-old writer from Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn - in part sums up his mission to make literature accessible to people who don't like to read. It’s an ethos at the heart of a cross-cultural movement that asks us to think again about our pre-conceived ideas about the intellectual and aesthetic.

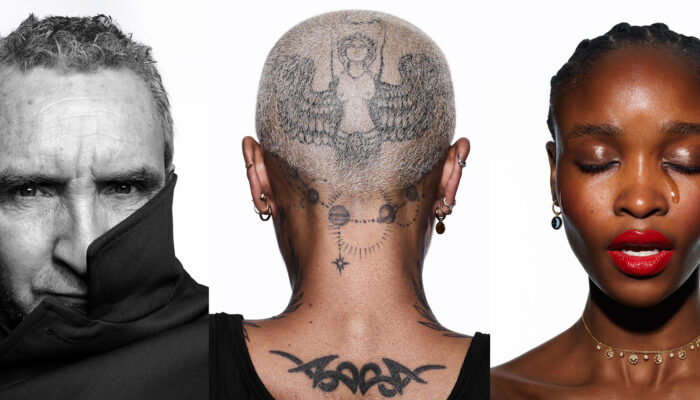

Words by Jolyon Webber - Photography by Ryan Plett

It all started a couple of years back with the simple post on his Instagram feed of a young man riding the subway very much dressed in the way a lot of young men are – Reeboks, headphones, backpack (McDonald’s drink carton stuffed in the back), t-shirt – immersed in Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, representative of cultures not clashing but embodied in the present. He hashtagged the post “Literaryswag” and has set in motion something both aesthetically and intellectually engaging.

Alongside news about his monthly neighbourhood book club, Literaryswag encompasses interviews with writers, celebrities and public figures, in which he asks them to list their three favourite writers and designers, and workshops with youth groups and in universities advocating for the power of language.

From there, Israel has, for me, become one of the most interesting and engaging commentators on the present state of American culture and racial identity. More than just a way of commenting on “the intersection between fashion and literature” – Literaryswag seeks to draw together many strands of popular culture to affirm that it’s okay to be politically engaged, well-read and well-dressed all at once.

THE FALL caught up with him recently to talk the genesis of the movement and its relationship to hip-hop, perceptions of the perhaps uneasy relationship between the cerebral and the sartorial, as well as his thoughts on the perilous state of American politics.

“It’s never lost on me how serious the work I do is, in the context of history… As much as what I do is fun and engaging, I know everything has come at a price.”

So was that first picture you took with the Literaryswag hashtag a lightbulb moment for you or was that point the culmination of thought processes percolating for some years?

It was just a right place right time kind of thing, sometimes things just fall in your lap. If I didn’t care about reading prior to that moment I wouldn’t have noticed that moment happening. But I had been so trained, at that time, I was always thinking about ways to make books cool. Because I’m a writer I don’t want to be an uncool person. I identify as cool and I want to make the things I identify with as cool. So when I saw that dude on the train it was just like, ‘this is it!’.

Have literature and fashion always been focal points of your taste in culture and expression?

I hadn’t thought to marry them together before that point. I had always seen them as peanut butter or jelly, not peanut butter and jelly. I thought – ‘so I’m smart but can I really be fly if I’m smart?’ And if I’m smart people aren’t really going to see me as fly because I’m smart. And if I’m fly, because so many people who are thought of as fly are seen as superficial and vapid, I’m going to get seen like that as well. I kept trying to run from one side while losing ground on another.

So when I saw the guy on the train it was a very sincere moment. And that’s at the heart of literary swag; the sincere want to engage with both the faculties of style and substance. I wanted to give something that isn’t about performing intelligence or style. All I’m really trying to show people is that there’s a world that exists in front of us that we’re not taught to see.

“As much as it seems like literature and fashion occupy two different ends of the spectrum, they actually affect culture in the same way.”

Why do you think there has been a reticence, on behalf of both fashion and literature, to embrace each other?

I think that fashion, more than literature, is consumer based. And to encourage an intelligent consumer base is to make it a lot harder for you to sell. A lot of fashion is predicated on a herd mentality, wanting you to feel like you have to have something. What’s interesting about Literaryswag is that as much as it seems like literature and fashion occupy two different ends of the spectrum, they actually affect culture in the same way. They get us to think about people and bodies, and they get us to think about each other in a way that creates a hierarchy. And that’s all cultivated around systems that are already in place. With Literaryswag I’m trying to, say that these things are part of a conversation that’s happening simultaneously.

No matter what the people at Public School or Pyer Moss create they’ll still get called ‘street’ brands or ‘urban’ couture. There are also definitions you get as a black writer. My writing is not literature, it’s black literature. It’s a way of pushing people into a corner and getting them to be thought of in a certain way and that limits the way people read it. And it limits the way people think about wearing certain brands.

Does it frustrate you that more people within popular culture don’t connect themselves to literature?

No, but I’d welcome it. There was the thing about Kim Kardashian starting a book club and people were hitting me up asking me what I thought about it. For me, anybody that’s going to help bring a person to a book is an ally to me. Even if that person themselves isn’t really about it, there’s someone that will do it sincerely. And that’s really what it’s all about.

It’s like a party. Sometimes I care less about how you got to the party but it’s more about the fact that you’re there. When you’re at the party you get to make the decision as to whether you want to stay or not. Some people are going to want to leave and that’s fine. Some people don’t care about every fashion brand but you can still know about it. That’s what I want for literature. Even if you don’t know about writing, or don’t care, at least you can know about it.

Do you consider the Literaryswag movement to be political? Aside from the aesthetic and intellectual element to it, further to that, is it in any way a commentary on the extent to which certain communities are educated?

Yeah, absolutely. I mean it’s never lost on me how serious the work I do is, in the context of history. One hundred, two hundred years ago I might have been murdered for even thinking of something like Literaryswag. My family is the product of the transatlantic slave trade where even looking at a book was punishable by death or they would have had their eyes plucked out for learning how to read. As much as what I do is fun and engaging, I know that everything has come at a price.

Think about hip-hop and how it was created. Hip-hop was created out of one of the most violent eras in New York City’s history. [Beatbox pioneer] Doug E. Fresh said the reason they learned how to beat-box and DJ was because the government and state cut all funding for instruments from schools. They had to use their own voices as instruments. Sometimes when we see the celebratory aspects of culture, we forget what the price of culture is. Who paid to get to the place where we can enjoy it? There’s a price with all culture. When you put on a nice jacket, especially when it’s handmade, you don’t know how many times that person had to prick their finger. For me, Literaryswag is political by design simply because this is a way to celebrate sacrifice.

“People are only now just realising that this country isn’t as tolerant as they thought it was. It has never been.”

There’s always been an easily accepted relationship between hip-hop and fashion – is that a basis from which you’re trying leverage some traction?

I’ve always explained it that I want to be to literature what Fab Five Freddy was to hip-hop, a cultural curator that explained to people what hip-hop really was. You need the curators who explain to people what they’re looking at, another set of eyes to tell how to see. With Literaryswag, at the first level I was the Fab Five Freddy but now I’m turning into someone like a Diddy in terms of the power I’m acquiring in the literary world. I’m starting to monetise and really own what I create, it’s kind of like that mogul culture but it comes out of something that I helped build and create. There’s nothing about literary swag that doesn’t remind me of hip-hop.

Hip-hop was built and created by people not in power and I think that’s why it’s something that people can universally connect with. People hear that music they hear the voice of what oppression sounds like but they also don’t hear the resonance through oppression. People need to hear that.

How do you feel about the state of American politics right now? I wonder if there’s any sense, in your opinion, that despite how dire the situation appears to be, it’s engendered conversations that might not have been had otherwise.

I’ll be honest, when Trump won, for me personally – I and want to emphasise personally – I wasn’t surprised nor was I hurt by it. There was more a sense of relief that he won. And I’ll explain why.

When Obama won, the country had delved into this very illusory self-perception that America had become post-racial. If you look at the narrative of the Obama presidency until Trayvon Martin was killed it was in bad taste to talk about racism and oppression. It was almost as if we were past that now. Then [the killing of] Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown happened and it becomes hard to ignore that. If Hilary had won, people would have said, ‘oh first we elected a black man and now we’ve elected a woman, everything is great…’ And there would have been no need to interrogate a system that was so deeply flawed. I think what Trump’s [election] has not allowed is for a lot of people, who wanted to feel better, to feel better.

For me, this country has never felt any different. We went through Bush, Clinton, Bush again, Obama – I don’t feel different. Because of my skin colour, my background and my income bracket I’m always at the mercy of people in power. When Obama won, there was like half a minute, where I thought that this means me too. But really, no – it just means him in a certain way. That’s not to say I didn’t identify with the victory or it didn’t have its own emotional gravitas but when I looked past that moment and its symbolism, I had to question what I really had. And it was a relief, knowing that I still had to do what I had to do. People are only now just realising that this country isn’t as tolerant as they thought it was. It has never been.

For more information on Yahdon Israel, visit his website here and follow him on Instagram.

All interior photography was shot at The Brooklyn Circus, our thanks to them.