We Want Quant – Mary Quant V&A Exhibition

Laura Miller takes us through the career of the marvellous Mary Quant, as seen through the new retrospective at London's V&A Museum

The Mary Quant exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum showcases the work of the revolutionary designer in an ingenious intersection with her cultural moment. Spanning the early 1960s through to the 1970s, the show is compiled from the Quant archive, the V&A’s own fashion collection and from the actual owners of various pieces — owners who had responded to the museum’s hashtag call: #WeWantQuant. These particular installations are accompanied by interpretive placards describing the wearer’s personal relationship to the pieces. They are clothing as memory, showing the potential of clothing to act as an agent of social transformation but also served with a side of sauce.

Mary Quant with Vidal Sassoon. Photograph by Ronald Dumont, 1964.

Seizing on the pervading feeling of the times, of a post-war generation seeking its own identity, Quant’s designs offered women a distinctive, vivacious and mobile look all of their own. She created minidresses with matching hot pants that brought knees and thighs out of hiding, foundation garments that were no longer ‘surgical,’ and famous swinging rain capes. The availability of new synthetic materials, like PVC, and stretch towelling opened up new avenues of creative possibilities for Quant and converged on the mood and the moment for the opportunities to use them.

Jill Kennington wearing Mary Quant white PVC rain tunic and hat. Photograph by John Cowan, 1963.

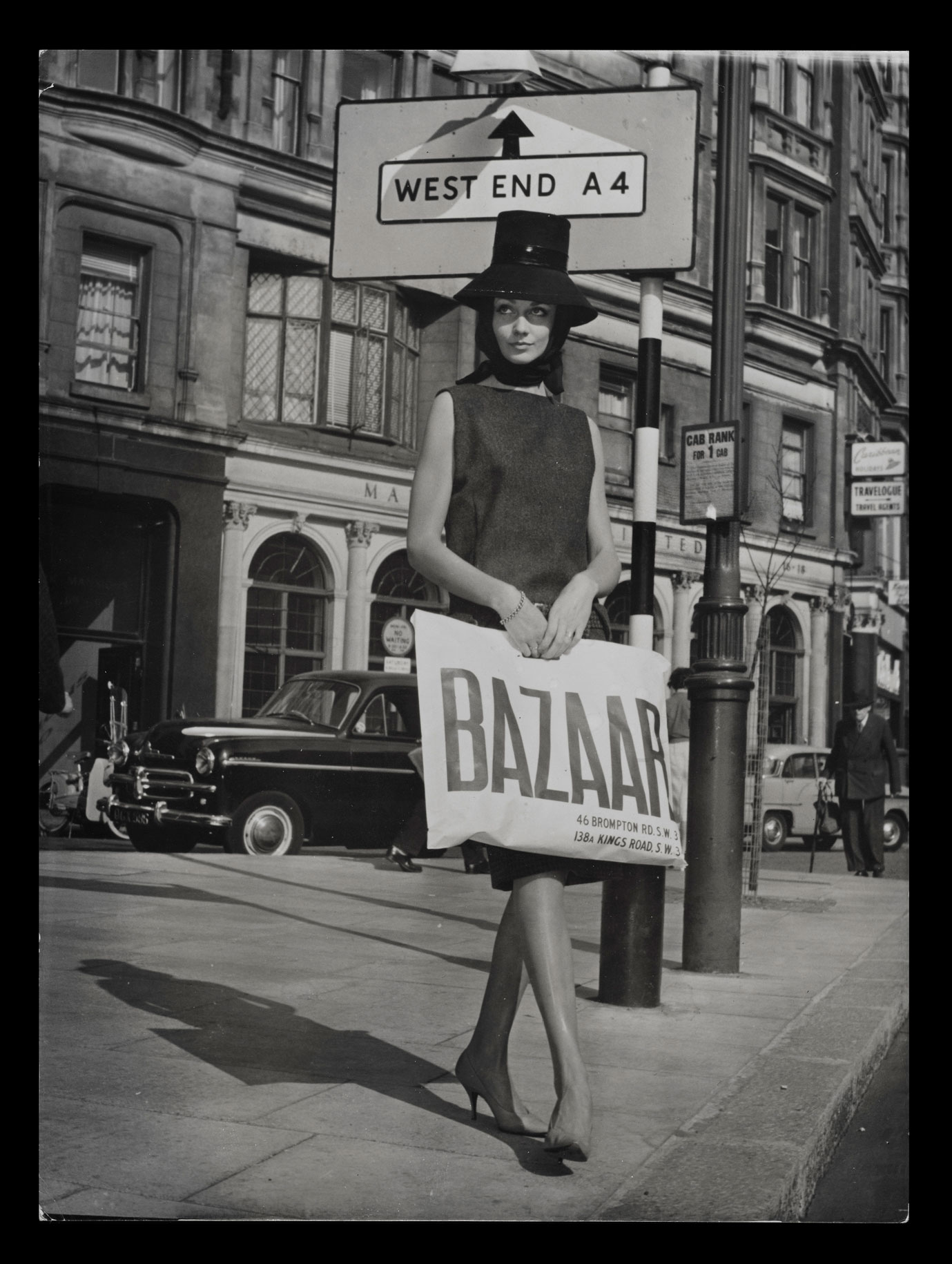

There’s a lot of conversation in today’s world about “building brands.” The V&A show is a demonstration in how Quant did exactly that from the ground up — but it wasn’t just a brand she built, it was an empire, spiralling out from her first boutique, Bazaar, in Chelsea. Quant allied herself with all the young fashion journalists and editors of the time, as well as with photographers like David Bailey and models like Jean Shrimpton and Grace Coddington. The marketing prowess of her label and its cheeky signature voice was driven by her husband, Alexander Plunket-Greene. Her shop window mannequins stood in gawky poses and rather than being sedate pageants, Quant’s fashion shows were ‘happenings,’ complete with live music, and models dancing, smoking and defiantly flashing their shorts. She commissioned strong, clear graphic designs for her logo on labels, stationery and black-and-white carrier bags that would be seen all over the streets. There was her totemic daisy flower, and a supremely catchy brand name — her own name — that defied class compartmentalisation. She struck, and maintained, a highly recognisable, slightly arrhythmic, perceptual rhythm.

Model holding a Bazaar bag c.1959. Mary Quant Archive.

At the same time that Quant’s designs were liberating the women’s movement — literally — there remained an undertow of distinct, self-conscious irony in some of the design titles. The “Bank of England” dress, the “Overdraft” waistcoat, and “Cheque Book” skirt were all designed to chafe against a different and older consensus of reality. In that era, women were still unable to access lines of credit without a male relative as a guarantor, or to have their own bank account without a male relative’s written permission. One of the exhibition’s displays reveals a custom order by Elizabeth Gibbons for a “Stampede” dress invoiced to “Mrs. J. Gibbons” — the customer’s identity as an individual submerged beneath her husband’s name. The material world couldn’t seem to move fast enough, yet, like a conjurer, Quant was doing her part in urging it forward, working with what she had at hand, to create the conditions to bring the new world about even faster. “A designer has to be someone who’s permanently bored,” she muses in one of the exhibition’s video installations – bored not only with existing design, but also with the cultural status quo.

Satin mini dress and shorts by Mary Quant. Photograph by Duffy, 1966.

How does one build an empire? Through forging relationships, and through licensure. Where others had specialised expertise, like the Alligator Rainwear brand of the time, Quant possessed the genius and foresight to create with them — or, as with Butterick Patterns, form relationships that allowed her customers to create the look for themselves. She always thought about and enacted ways her brand could become pervasive and stronger without ever sacrificing the quality. For example, Quant was one of the first to start and sustain a mass production/distribution model with the Ginger Group diffusion line. Here she produced ranges of shoes and leg wear, “Q-Form” foundation garments and make-up sets complete with application instruction sheets to enable her customers to create an all-in-one total, harmonious look. Her efforts went on to foment a fashion revolution that proved to be even beneficial for Britain’s wider national economy.

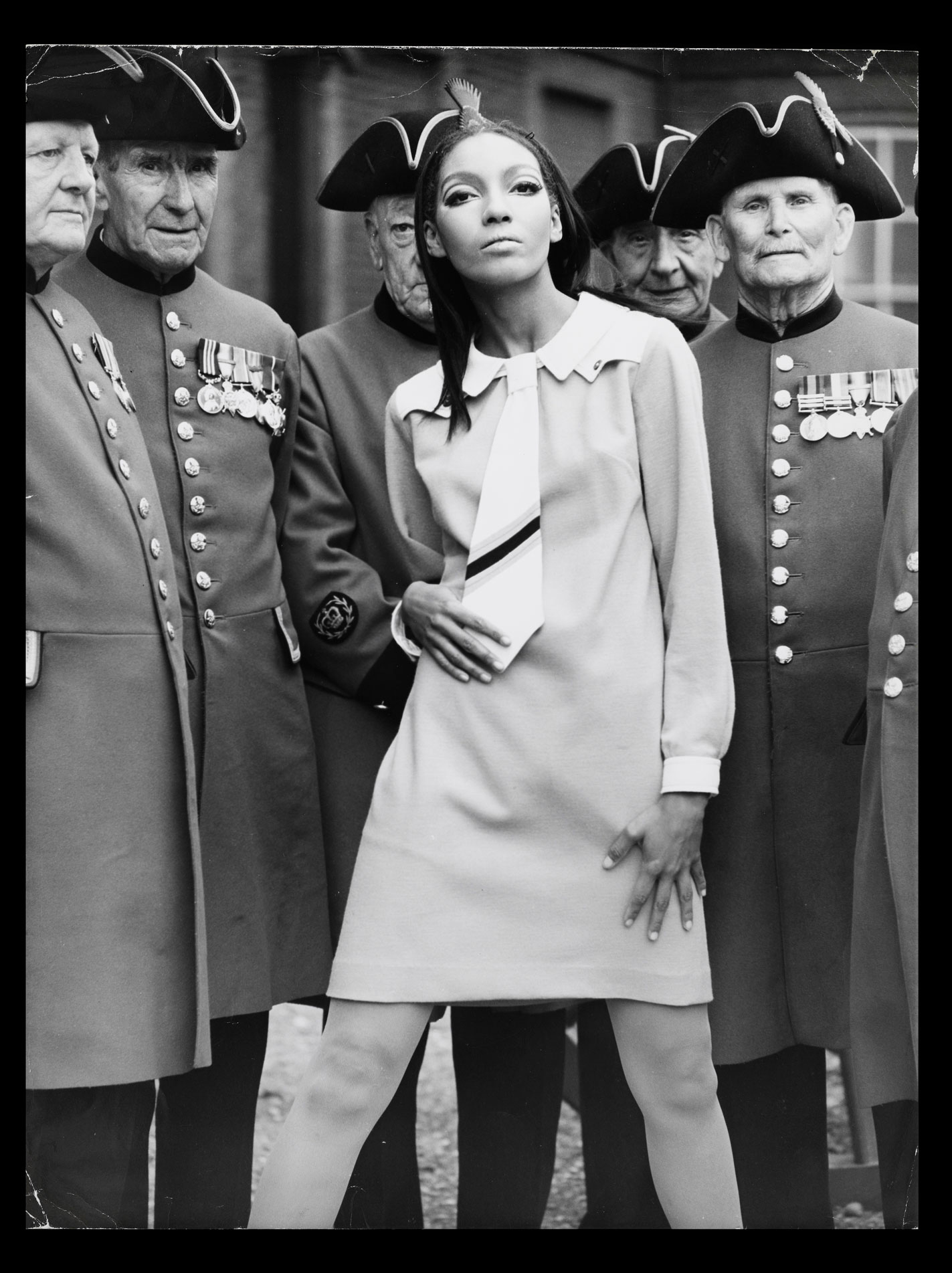

Kellie Wilson wearing tie dress by Mary Quant’s Ginger Group. Photograph by Gunnar Larsen, 1966.

Unlike today’s throwaway fast fashion, many of Quant’s garments still exist and have been contributed with pride to the Quant exhibition by the women who wore them and are excited to be associated with them. Quant’s pieces have also become a way of telling their own stories. In one of the show’s rotating videos, Quant reflects on her process and her own personal standards of excellence and longevity: whenever she creates a piece, she says, she asks herself, “Is this as good as a pair of Levi blue jeans?” For her, empire is about building something substantial, something enduring, and also something that changes the state of things from the way they were before. All things that can be seen and documented throughout her fascinating exhibition.

Mary Quant and her models at the Quant Afoot footwear collection launch, 1967. PA Prints, 2008.

The Mary Quant exhibition is on now until 16 February 2020 at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, Knightsbridge, London.

Laura Marjorie Miller is an art and culture writer

Read our other fashion exhibition reviews here.