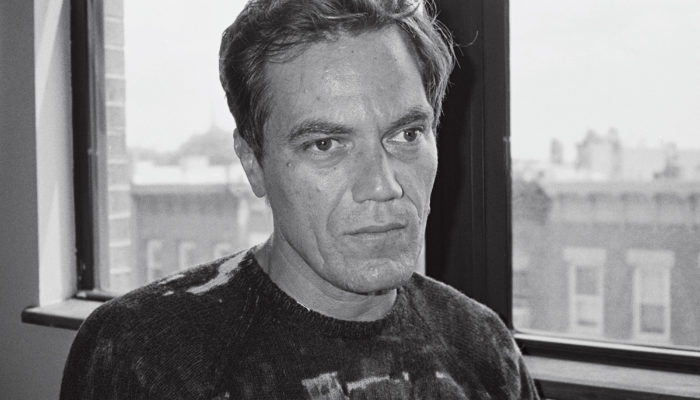

Reluctant Hero, Michael Shannon

Photography by Michael Stipe | Styling by Julie Ragolia | Words by Tom Shone

People say you are intimidating, I tell Michael Shannon. “Well, fuck them,” he growls. “Where do they live?” He doesn’t laugh, for Shannon doesn’t laugh at his own jokes, if jokes they are: more a stream of sardonic-absurdist observations on the world, like a man amusing himself while everything around him goes up in

flames.

At 6ft 4in, the actor is tall but stooped, his centre of gravity slightly off, walking with a slight limp, as if dragging a sackful of troubles behind him. His face is creased and rough-hewn, with a broad, overhanging brow, eyes set far apart, giving him a slightly buggy look, and a hard-set stern jaw that rarely smiles. Google him and a Tumblr – Michael Shannon Tries to Smile – comes up (the site’s manifesto: “I love Michael Shannon, I wish he could be happy!”). Hence the “intimidating” tag. “In every role, Michael Shannon makes you wonder, makes you want to know, what the hell is eating him,” wrote New York magazine’s film critic David Edelstein of his Oscar-nominated performance in Sam Mendes’s 2008 Revolutionary Road as a truth-telling headcase whose X-ray insights threaten a marriage.

Above all clothes by Marni; Main image sweater and trousers by Berluti, socks by Paul Smith, shoes by Grenson.

“Shannon does not look alien, exactly, but never, even in company, do his characters seem like happy members of the human tribe,” wrote The New Yorker’s Anthony Lane of his performance, also Oscar-nominated, in Tom Ford’s Nocturnal Animals, as a Texas detective at the end of his rope. Here are some of the other adjectives that have been applied to his performances: taciturn, spooked, hard-bitten, haunted, heartbreaking, terrifying. “It’s certainly a conversation I’ve had more than once,” he tells me. “I don’t know what to say. I mean, I get mugged just like everyone else gets mugged. I don’t have any guns in my house. I’m a pretty docile individual. I don’t really understand it.”

He scratches his chin, his irony levels indecipherable. Talk to his co-stars and a different picture emerges: of much sardonic mischief and dry-as-a-bone humour on set. On the set of Boardwalk Empire, where Shannon spent five seasons playing zealous Prohibition officer Nelson Van Alden, the director once asked him to do a take a different way. Loud enough that he turned heads, Shannon retorts: “You want me to cry? Let me understand, you want me to CRY?” The whole set stops. Shannon holds for a second, lets the director sweat, then: “Oh, I’m just fucking with you.”

While publicising Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice – a film he admitted to falling asleep during while watching on a plane – Shannon livened up a dull press interview with a tale about getting stuck in his trailer, unable to open the door with the flippers he wore on his hands. The story went viral – why would General Zod be wearing flippers? – before it was revealed that Shannon was joking.

“I think my default point of view, even when I’m at work or no matter what I’m doing, is basically that this is all ridiculous”

“It’s not like I show up with a box of snakes or something,” says Shannon, who arrives at a coffee bar in Williamsburg on a sweltering New York day, dressed in navy T-shirt, fitted grey slacks and a pair of colourful striped socks of a kind he’s collected for years. Making movies can be a pretty tedious business, he tells me. “It’s like being in surgery all day. Everything is so delicate. There are some days where you’re like, ‘Fuck this. I don’t want to do this scene.’ Or, ‘I don’t want to sit around for an hour, waiting for them to figure out what’s wrong with their lights.’ If I see the opportunity to crack a joke, I do. I think my default point of view, even when I’m at work or no matter what I’m doing, is basically that this is all ridiculous. It’s all completely absurd and it’s not that I have to force myself to take it seriously, but I certainly enjoy not taking it seriously. My favourite writer of all time is Eugène Ionesco, who’s one of the godfathers of the Theatre of the Absurd. I’ve done his plays. The only play I ever directed was a play he wrote, called Hunger and Thirst. It’s probably my favourite play.”

He’s pleased to be out of his apartment in Red Hook, where he lives with his girlfriend, actress Kate Arrington, and their two young daughters: a few blocks down, a shipyard has been converted into a track to race Formula One electric cars. “They’re expecting a couple of hundred thousand people to pass through our neighbourhood today to see this thing.” Wearing shades when he first arrives, he removes them after a few minutes, as if sensing that the coast is clear, and makes only intermittent eye contact. You sense a shy, rather gentle giant beneath the dark, biting humour. Some other adjectives that his performances have attracted: detailed, subtle, moving, thoughtful.

Top by Acne Studios, trousers by Ermenegildo Zegna Couture.

There’s a streak of protectiveness that comes through in films such as Jeff Nichols’s Midnight Special, one of five films he has made with the filmmaker – including Shotgun Stories (2007), Take Shelter (2011), Mud (2012) and Loving (2016) – in which uncanny happenings, from murder to intimations of apocalypse, unfold against a backdrop of trailer homes, pickup trucks and Kmarts in the American South and Midwest. “I like worrying about you,” he tells his son in Midnight Special, using the spare, unadorned but affecting idiom of all of Nichols and Shannon’s collaborations together.

“The person I most admire in cinema history is Jimmy Stewart, probably,” he says. “There’s this kind of understanding among human beings, I guess, that words are the primary way we communicate with one another. And I hate to say this to a writer, but that may not be true. That words ultimately may be one of the less effective ways we have with communicating with one another. A lot of times, as an actor, you can use dialogue as a way of avoiding what the real story is. It’s very easy to talk and be thinking about something other than what you’re talking about. Look, it’s an uncomfortable thing being a human being, isn’t it?”

“You mean being in contact with one another?” I ask. “Always. The list of the comfortable parts is far shorter than the uncomfortable parts. When you hear that an iceberg that weighs one trillion metric tons has broken off from Antarctica and is floating God knows where to do God knows what, that’s an uncomfortable feeling. And it’s always in the back of my mind, whether I’m sitting here doing an interview with you, or walking around the park, looking at children playing soccer, or wondering what I’m going to order to drink at the bar. In the back of my mind, I’m always like, ‘What’s that ice cube doing right now? I wonder where it’s heading. Is it melting? How much longer do I have in Red Hook before it’s underwater?’ Things like that.”

This is an extract of an article taken from the latest issue of THE FALL available to purchase from nationwide retailers and our Shopify store here.