Nobuyoshi Araki, Sex and Sentimentality

Divisive, prolific, pornographic, the oeuvre of Nobuyoshi Araki spans over 500 books and innumerable exhibitions. Shooting flowers resembling genitalia, and countless women bound from the ceiling with bondage rope, the indefatigable Japanese artist is one of the world’s most successful, outrageous and transgressive photographers of the past 50 years.

Words by Max Grobe

Araki’s style has always favoured the medium of film (his views on digital photography are pattered with disinterest, and later in life, absolute contempt) and his lens is charged with an eroticism that disrupts the balance of our public and private lives. Although he may have often infamously equated his camera to his penis, and once, “a cunt”, Araki is not lecherous by virtue of lechery’s sake and neither are his photographs. Araki’s so-called perversions have always been for life itself.

His career began to permeate contemporary culture in the 1980s, during the golden age of Japan, or the ‘bubble’, a boom of economic growth and investment in technology that birthed a new sex industry and carnal nightlife in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district. Catering to almost every fetish imaginable, and a popular stop-off for wily commuter-amateurs, the once hidden world of bedroom desire was documented relentlessly by Araki for Photo-age magazine and can now be seen in his book Tokyo Lucky Hole, published by Taschen.

A frenetic hedonist (and dedicated cat-lover) his aesthetic of kinbaku (a style of Japanese rope bondage), flowers, cemeteries and X-rated sex shows reveal the joys of being alive, of seeing, and being seen. His penchant for bondage, which in another context could hinge on misogynistic or oppressive (particularly to Western eyes) is subversive. Araki has said that by tying up the body he frees the soul. The intricately bound women in his photographs, most of whom are from Tokyo, do not look into the camera with a Terry Richardson-esque deer-in-headlight paralysis but with strength, desire and a consent to be seen whilst hung from the ceiling, emanating a nuanced vulnerability which doubles up as power.

At the end of last year, Araki’s kinaesthetic visuals were tapped by cult streetwear label Supreme for a collaboration which he, in a typical autonomous fashion, shot the campaign for. Japanese it-girl and model du jour Kiko Mizuhara was photographed with a plastic crocodile wearing the Supreme hoodies and t-shirts featuring graphic prints of Araki’s suggestive thorny roses. It felt like the perfect collision of downtown New York’s “I don’t care what you think” street style with Tokyo’s sensibilities of lo-fi, imperfect perfection.

Like superfan and similarly mononymed outlier Bjork (who requested Araki shoot her album cover and sleeve for 1997 record Telegram) Araki has tirelessly challenged his artistic sensibilities, even the loss of vision in his right eye in 2014 could not deter him, but instead provoked “Love On The Left Eye”, an exhibition of his photographs with the right side of each image covered by blackness. With Araki, we are always invited to consider how he sees things, not just in an aforementioned literal sense, but how his worldview and pursuit of imagery encourages us to seek out great, occasionally obscene and beautifully simple encounters of our own.

His long career has calcified a certain distaste for journalists, or people who insist on asking him the same questions, making him in spite of his huge body of work, still something of a mystery. As he ages, his work began to touch on inevitable loss and fragility of life. As demonstrated by his touching photo book about his marriage Sentimental Journey, Araki opens the book with images of his wedding, portraits of his wife Yoko naked on their shared hotel bed before jarring the viewer with photographs of her body being wheeled into a morgue after losing a battle to cancer in 1990. The photo-book ends with pictures of his cat Chiro, warmly known as “Japan’s most famous cat”, who died in 2010.

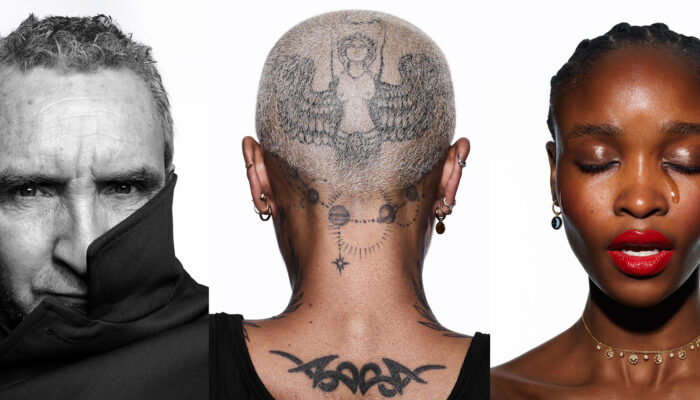

At the core of Araki’s imagery is an intense kind of intimacy that bleeds between sexual arousal, emotional catharsis and a disregard for societal norms. What we can appreciate about Araki, who’s latest exhibition Photo Crazy A sees the iconoclast return to the traditional form of Japanese calligraphy, is how the artist opens visual channels to divert the way we see, the way we are seen and the way photography can be initiated as an explorative, rewarding and shamelessly titillating medium between the two. Now 77, Araki photographed here at his latest exhibition Photo Crazy A in Tokyo, the artist’s striking silhouette and ebullient energy remains as memorable and impactful as ever.