Mr & Mr Smith

The young star of Baz Lurhman's short-lived hip-hop saga The Get Down was photographed by rap royalty the RZA for THE FALL's latest issue. Meet the relaxed charm and charisma of Justice Smith.

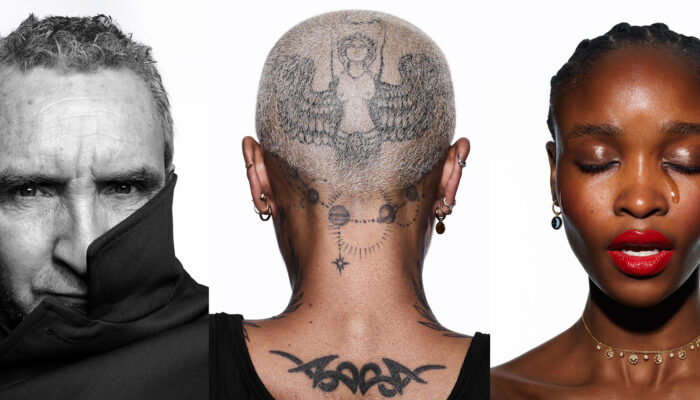

Photography RZA | Styling Julia Ragolia | Words Amy Marie Slocum.

When hip-hop pioneer Grandmaster Flash was asked in a recent interview whether he knew that the techniques he was pioneering in the 1970s – isolating drum solos and playing them back to back on two turntables with a jerry-rigged fader – would revolutionise music, he responded simply, “I was in the moment.”

That the 22-year-old Justice Smith says the same thing concerning his career-making role as Ezekiel in The Get Down – the Baz Luhrmann-directed Netflix extravaganza about the birth of hip-hop – may speak to why the legendary director chose Smith, an actor with four credits to his name at the time, for his show’s protagonist.

I drive out to Malibu to meet Smith on a Thursday afternoon, where he is being photographed at a gorgeous beach house perched precariously between the Pacific and the Pacific Coast Highway by none other than hip-hop legend RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan. Stepping into the airy rooms as he is getting a couple of last shots in, I overhear the rapper/actor/filmmaker/photographer making his subject laugh with a story about getting arrested 19 times. Smith is not as short as most Hollywood actors and thankfully not as self-serious as his Get Down character Ezekiel “Books” Figuero, a half-black, half-Puerto Rican troubled poet who finds an outlet for his talents in the nascent hip-hop scene in the late-’70s Bronx.

Main image: cardigan by Ermenegildo Zegna Couture. Sweater by Stella McCartney. Hat by The Kooples. Above: all garments by Comme des Garçons Homme Plus.

“I’m very fortunate that I live in this time where I’m still able to work and I’m still able to get stuff that means something to me and promote what I am and what my family is„

Coat by Dries Van Noten. Waistcoat and T-shirt by Levi’s. Trousers by Bode.

The storied rise and fall of The Get Down is an allegory for the chaotic post-prestige television world that we currently find ourselves in. With a celebrated film director’s first TV foray and a reported budget of $120 million (about £93 million) for the first season, it was one of the most widely publicised and critically anticipated releases last year.

Richard Lawson, writing for Vanity Fair about the series, expressed the hope that the director’s penchant for grand opening scenes that he calls “discombobulating and unpleasant” might be served by a longer format, giving Luhrmann room to “charm and amaze”, but in the reviewer’s opinion, the three episodes he watched failed to deliver on that promise. Ultimately, The Get Down was not renewed for a second season by Netflix. In a lengthy Facebook post, Luhrmann stated that he declined to sign on for another season due to other film commitments.

Jacket by The Kooples. Foulard by Officine Générale.

“When you’re young and you see yourself represented on

television, it goes a long way – you don’t feel like you’re left

out of society„

Jacket by Off-White, coat and sweater by Alexander Wang. Trousers by Comme des Garçons Homme Plus.

Born to two musicians in Anaheim, California – Smith’s mother a white, Canadian-born singer, and his father an African-American singer and bass player – Smith tells me he grew up poor with eight brothers and sisters from various stepfamilies in a highly creative home. “I grew up going to [my parents’] shows and being on stage with them and being in the green room while they performed,” he tells me. “My sister’s also a singer, but I was the only person who wanted to be an actor.” It’s evident that Smith had an idyllic youth, despite not having a lot of money.

“I always wanted to be an actor,” he says, “but as a kid I wanted to do it all. I wanted to write, direct, and I thought I could be a visual artist as well, so I used to paint all the time.” That creative omnivorism has paid dividends for Smith, who is unusually thoughtful for his age and switches effortlessly between ebullient and dead serious when discussing things like the state of black representation in film and television.

In an interview last year with Vulture, it was stated that Smith “almost lost himself” in the role of Ezekiel. When I bring this up, he tenses. “I did that interview where I talked about how actors use The Method for publicity,” he says. “I think each actor has his own process, but something rubs me the wrong way when it becomes a topic of conversation – how you stayed in character the whole time. I said that in this interview and then it bit me in the foot when the article came out.”

Was the article inaccurate in claiming that he used method acting in this role? “I had my own process for approaching Zeke and for approaching the piece,” he says, “but I never really wanted to talk about that or promote that that’s the most important part of the performance, because I think an actor is more powerful when they don’t show their work – where their work is shown in the performance and you don’t need to see all the steps that they took to get there.” I ask Smith if he looks back on his time as Ezekiel with fondness or with a twinge at the pain he went through. “No,” he says with relish, “the pain is my favourite part! It was hard and there was a lot of blood, sweat and tears, but I look back saying, ‘That was an amazing opportunity that I had to do that.’”