Kaveh Golestan, Prostitutes of Iran

Words by Ammar Kalia.

In the years between the 1953 American and British coup in Iran and the Islamic Revolution of 1979, when the reactionary Ayatollah Khomeini came to power, Iran underwent a rapid process of modernisation. The period saw an apparent slackening of religious prohibitions on women’s dress codes, yet with a continued commodification of their bodies and sexual practices. This tokenistic liberation undermined by reinforced subjugation is nowhere clearer than in the walled-off ghetto of Shahr-e No, Tehran’s red light district.

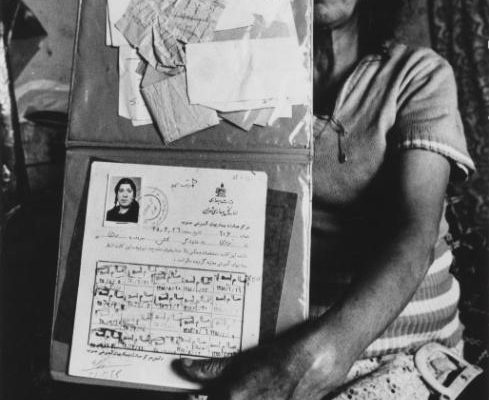

Home to some 1,500 women, the inner confines of Shahr-e No have passed through history largely undocumented after the area was purposefully set alight during the 1979 Revolution. The fire was not extinguished and there are no records of how many women died in the blaze. Even those who survived, such as the three sex workers Sakineh Qasemi, Saheb Afsari, and Zahra Mafiha were promptly arrested and executed – the first official executions of women by the new Islamic Republic.

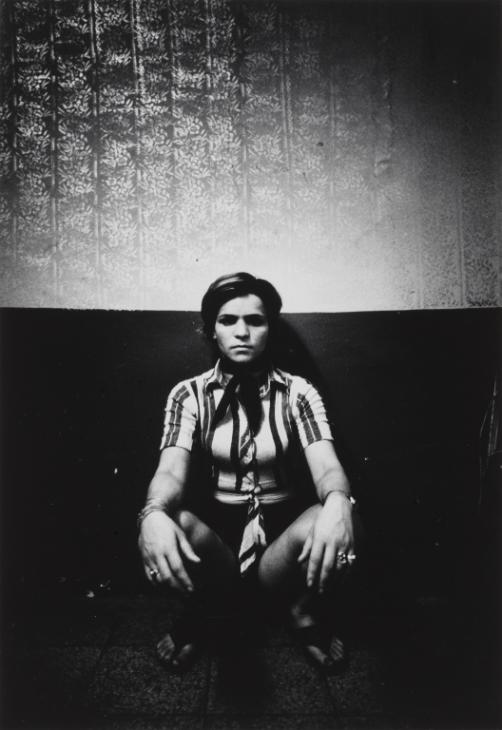

The photographer Kaveh Golestan, however, spent two years in Shahr-e No before its collapse, gaining the trust of its residents in order to faithfully document the lives and humanity of the workers there. A selection of his black and white prints from 1975-7 is currently on display at The Tate Modern, comprising the first room of works to be held in the permanent collection by an Iranian artist.

For Golestan, these images had a political as well as aesthetic charge. He commented, “I want to show you images that will be like a slap in your face to shatter your security. You can look away, turn off, hide your identity […] but you cannot stop the truth, no one can.” Valuing this idealised, expository function of the camera above all else, Golestan’s images do not shock at the level of sensationalism but form a lasting impression owing to their sensitivity and intimacy.

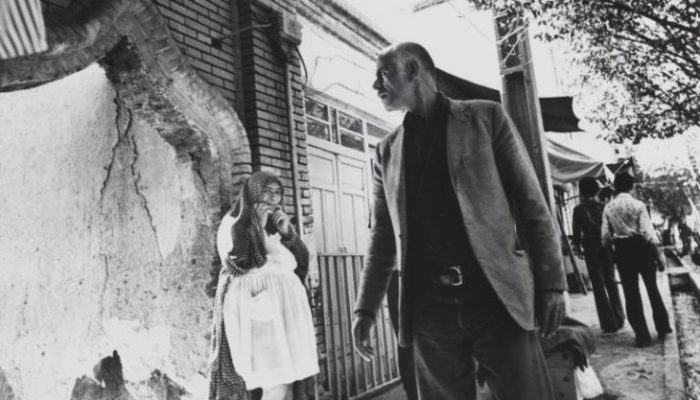

All of the 19 images on display are ‘Untitled’, placing emphasis on Golestan’s subjects, rather than an imposed context. Beginning with images of street life in Shahr-e No, we see vernacular impressions of the day-to-day in this ghetto; merchants selling their wares and walking the streets. Yet, the sexual commerce is a consistent presence, with Johns soliciting for sex or the street-stains of bodily waste eerily present in the background.

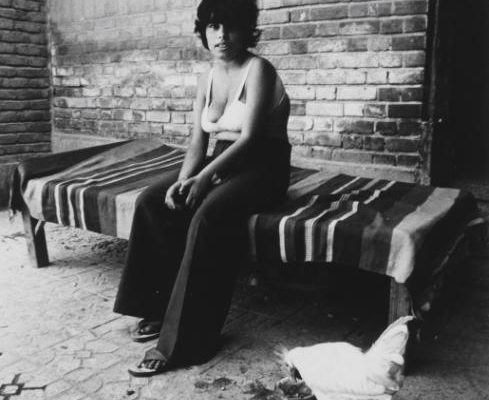

Moving inside for the majority of the series, Golestan frames the sex workers within the darkened confines of their rooms/workspaces. Some of his subjects stare out confidently at the camera, staging their presence in relation to wall hangings and neon decorations, while others stand with their face to the wall, shielding their identity from the camera’s intrusive gaze. In one image, all we see is a rumpled bedspread and the accompanying detritus of the sex worker’s room, poignantly symbolising the destruction of these women’s private lives in their claustrophobic existence. The camera merely documents that which is already public.

Golestan first exhibited these images in Tehran in 1977, alongside two other series of children and construction workers, but the show was promptly shut down by the authorities. His truth-telling was too candid for an authoritarian government on the brink of collapse.

With the women of Iran now protesting once more against the prohibition of the hijab, Golestan’s sensitive and honest portrayal of the human condition pushed to its extremes is more vital than ever.

Kaveh Golestan’s Prostitute Series is on display in the Artists and Society exhibit in The Tate Modern.