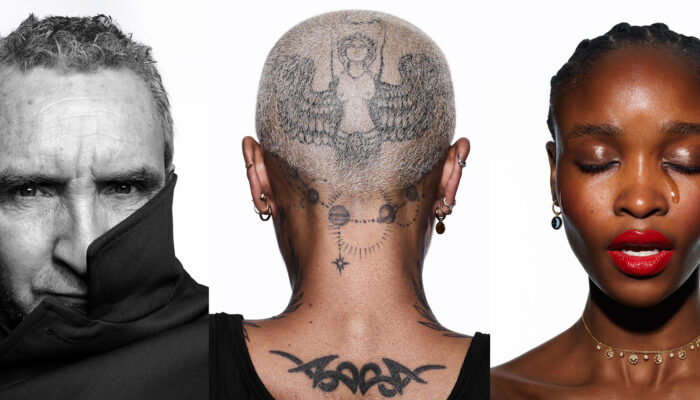

Duane Michals, Portraits

Maya Angelou, 1970s.

Over the course of an ongoing 55-year career, Duane Michals has constantly reinvented himself and, in many respects, the conventions of the narrative photographic story, never content to settle on the limitations imposed by technology or taste. Through staged photographs, his writings on the subject, he has drawn, painted and manipulated photographs in ways that prove as influential today as they were when he first began. As he himself once stated. “My pictures are more about questions, not about answers.”

Michals first made significant, creative strides in the field of photography during the 1960s. In an era heavily influenced by photojournalism, Michals manipulated the medium to communicate narratives. The sequences, for which he is widely known, appropriate cinema’s frame-by-frame format. Michals has also incorporated text as a key component in his works. Rather than serving a didactic or explanatory function, his handwritten text adds another dimension to the images’ meaning and gives voice to Michals’s singular musings, which are poetic, tragic, and humorous, often all at once.

Susan Sontag, 1959.

“I think photographs should be provocative and not tell you what you already know. It takes no great powers or magic to reproduce somebody’s face in a photograph. The magic is in seeing people in new ways.”

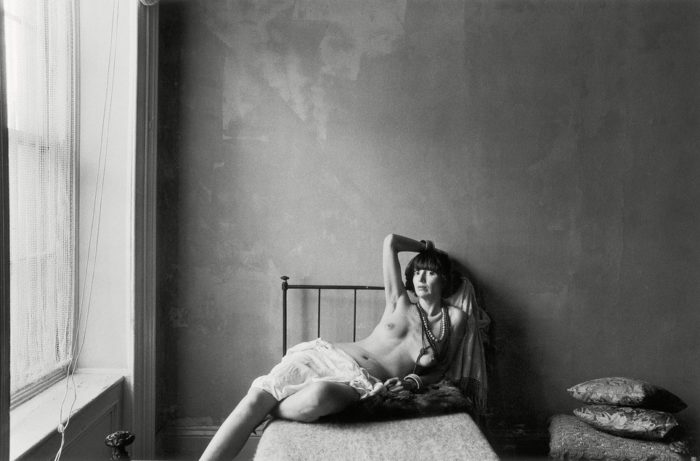

Deborah Turbeville, 1976.

Born in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, after taking art classes at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, he attended the University of Denver, where he received his undergraduate degree in 1953. After his military service ended in 1956, Michals moved to New York where he studied at Parsons School of Design and worked as a graphic designer for Dance and Time. A three-week tour of Russia in 1958 with a camera borrowed from a friend marked the beginning of Michals’ artistic career, although he still accepted commercial photography assignments. His Russian photographs are portraits, while his images from the mid-1960s catalogue deserted sites in New York.

In 1966, Michals started to structure his photographs as multiframe compositions, with subjects enacting set narratives. He began writing captions in the margins of his photographs in 1974 and incorporated painting into his treatment of the printed images in 1979. Books such as Salute, Walt Whitman (1996) veer away from the artist’s characteristic interest in issues of mortality and sexual identity and instead address textual sources for subject matter. Michals received ICP’s Infinity Award for Art in 1991.

Joan Didion, 2001.

Michals’s narrative pieces rely on the sequencing of multiple images to convey a sense of alienation and disequilibrium. In his world, the literal appearance of things is less important than the communication of a concept or story. In his portraiture, however, Michals relies wholly on his subjects’ appearance and self-chosen poses to establish their identity; asserting that “we see what we want to see” and that photography is incapable of revealing a person’s private nature, he eschews his usual interest in Surrealism, dreams, and nightmares in favour of a more direct approach.