Clubbed, A Visual History of UK Club Culture

Words by Ammar Kalia

The history of dance music in the UK has always been one of tribal affiliations. Since acid house migrated from American shores in the late 1980s and birthed the rural hedonism of field raves, to the Thatcherite rebellion of illegal warehouse parties, the urban freneticism of Jungle and the urbane glamour of 2-step and garage, loyalties to each scene have been visual as much as aural.

From bucket hats and ecstasy-fuelled neons for the raving crew to MA2 bomber jackets and Goldie’s grills for the junglists, and printed Moschino and Versace for the 2-steppers, the visual aesthetic extended beyond fashion to the branding of the nights themselves. In the movement from parties being communicated via last-minute text to your Nokia to regular inner-city nights, the flyer and the poster were key for extending reach beyond the ‘underground’ circle. Branding became a coded badge of the underground, avoiding the taint of commercialism while keeping the dancefloor open to newcomers.

In homage to these visual cultures, graphic designer Rick Banks has put together a bound collection of formative designs from iconic UK nights, Clubbed.

“Dance music was hugely influential to me when I was growing up, it was one of the biggest reasons I got into graphic design”, explains Banks, “I was too young to go to the majority of clubs in the ‘90s but it was the designs that made me buy the CDs, vinyls and merchandise.” The aesthetic stood in for the party when it was inaccessible, rather than a mere advertising supplement.

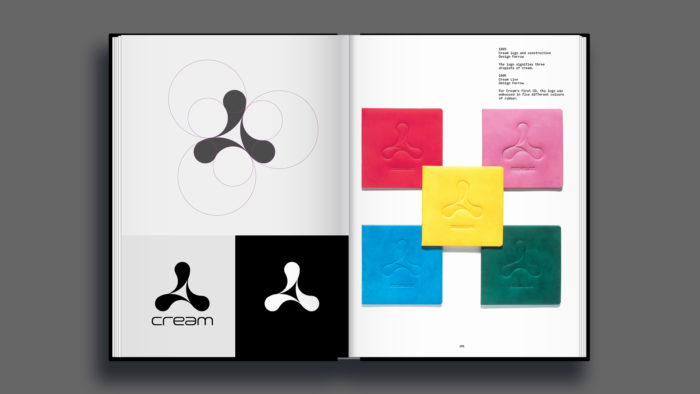

Testament to the power of the image is the resonance of designs like those of Ibiza pioneer Cream. Despite its modern-day similarity to a fidget spinner, the endless curves of the logo not only symbolise three droplets of cream but are also reminiscent of the waveform trance synth sounds played so often at their nights. Banks admits “I wanted to shave the Cream logo into my head as a teenager! That’s how strong the logo is. It’s timeless.”

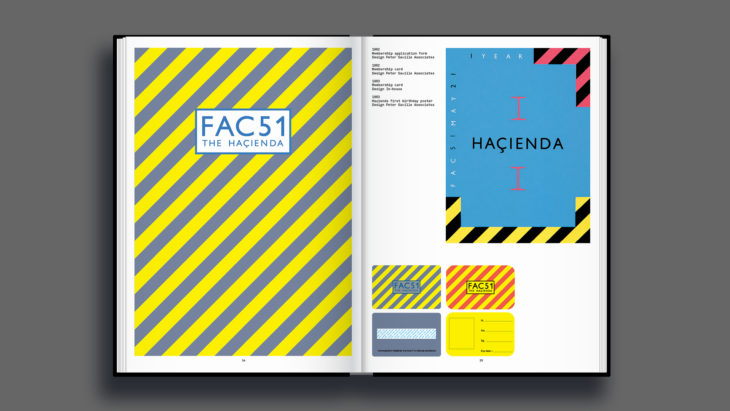

Other imagery sourced for Clubbed includes the lively neon yellow stripes of Peter Saville’s Haçienda designs. Equal parts invigorating and nauseating in its vibrancy, the design was an unmistakable counterpart to the propulsive sounds of the club: New Order’s frantic trauma, The Fall’s nonchalant poetry, and The Happy Mondays’ sloppy excess.

Digitizing designs from the Haçienda and Cream archives for the first time for Clubbed, Banks admits that if the modernising process hadn’t occurred, “they would be lost forever”. Rather than revelling in nostalgia, though, Clubbed also features aesthetics from 21st Century parties.

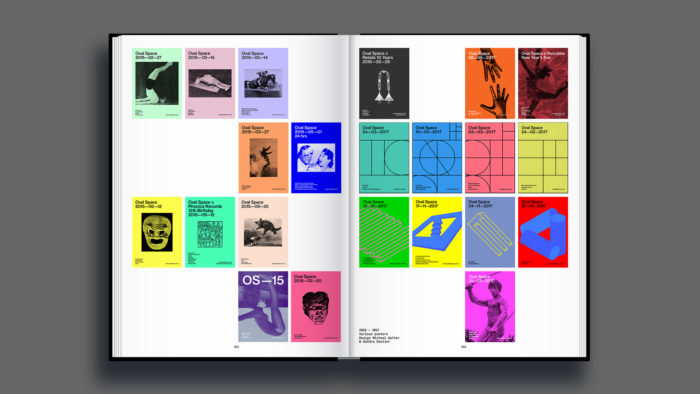

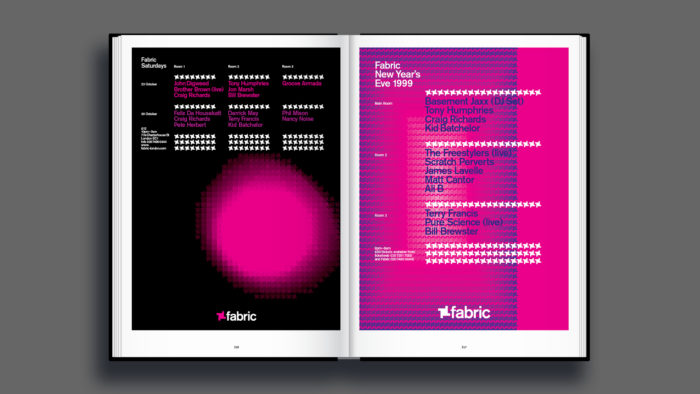

Despite the fact that in the digital age branding has become ubiquitous to the point of inanity – “with the internet and smartphones equipped with instant notifications the art of the flyer has died”, Banks says – nights like Jackmaster’s Numbers and venues like Oval Space, Fabric and Printworks still provide instantly recognisable designs. “They all have a unique style and voice; whether through clean minimalism, fluorescent illustrations or bonkers photography”, Banks explains.

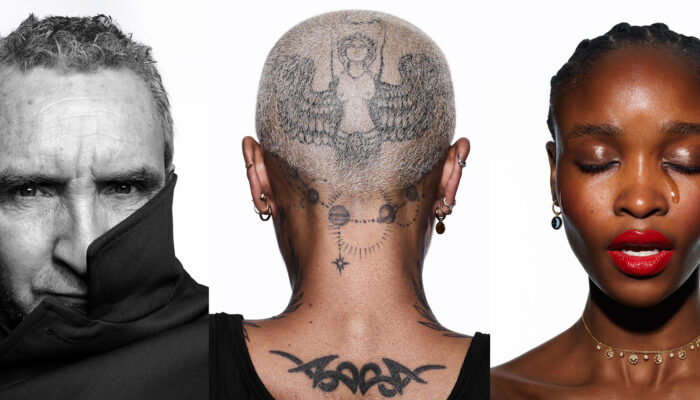

Taking London mega-club Fabric as a point of reference Banks enthuses, “I loved how Fabric abandoned the graphic approach in favour of a more surreal aesthetic. By using photography, set design and model-making their posters created their own visual world and sometimes they don’t even use the Fabric logo which makes it even more impressive.”

So, the power of the visual extends beyond the logo to the codified affiliations of the scenesters themselves. If you know, you know – without needing to look too carefully. With streaming platform Boiler Room applying the same attention to visual detail without operating from a conventional club-space, club cultures will continue well into the boundless internet age.

For more information on the book and how to purchase, visit the Kickstarter page.