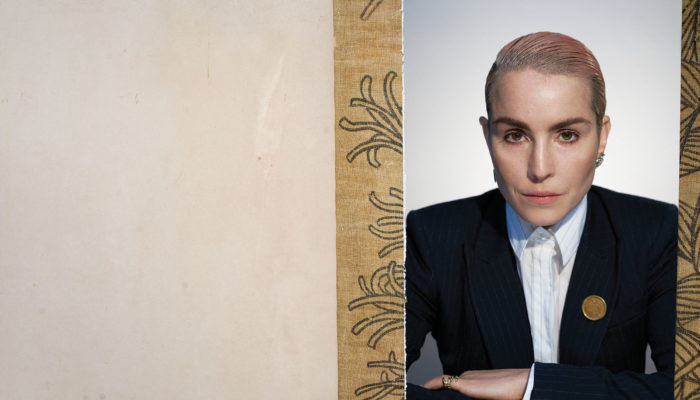

Attitudism, Noomi Rapace

Photography by Mark Lebon | Styling by Elgar Johnson | Words by Hannah Lack

As a hyperactive child growing up on a Swedish farm, Noomi Rapace would jump on a horse when she needed space to think. Now that she’s a west Londoner, she’s swapped the horse for a vinyl-black convertible. “My mind is so busy, driving is a kind of meditation for me,” she says, steering us down Ladbroke Grove in a rare patch of London sunshine. “I’ve always been hyper. I go to bed late, I’m up early, I’ll work out once or twice a day… I’m a weirdo, I just don’t sleep a lot.” Today, with her bleached hair and cliff-edge cheekbones, cartoonish-red Moschino coat and vintage red leather trousers, the chameleon actress resembles a Nordic Akira. “I have very strong feelings about what I wear,” she says, pressing the accelerator down with a patent leather boot. “It changes everything – how I feel, how I walk. For me, fashion is a shield, a protection, a second skin.”

On the red carpet, Rapace is every bit the megawatt movie star – in scarlet Vivienne Westwood at Cannes, or channelling Clara Bow at the 2017 BAFTAs in faux-fur Gareth Pugh. But on set she’s happiest in the trenches, playing the scrappy underdogs, misfits and survivors closest to her heart. From icy punk avenger Lisbeth Salander in the Millennium trilogy, battling Sweden’s dark heart with a Taser gun and colossal IQ, to the indomitable astronaut who terminates her alien baby with a wince-inducing C-section in Ridley Scott’s Prometheus, when Rapace is onset, her best angle doesn’t come into it. “Fuck, no!” she laughs. “Why would you be wearing mascara in space? Personal vanity never dictates anything when I step into a role. I’ll look like shit. Whatever I do, I go for it 100%.”

Main image: Jacket by Theory, shirt by Neil Barrett, vintage brooch by Judy Blame. Above: Suit, waistcoat and brooch by Dsquared, shirt by Theory, tie by Paul Smith, shoes by Guiseppe Zanotti.

“I love people who are colourful, with strong opinions – Vivienne Westwood of course, because she’s an old punk! My biggest icon”

The indefatigable 37-year-old is notorious for diving so deep into her characters it’s sometimes a struggle to surface. When she takes on a role her commitment is total: it’s not often you hear of an A-lister cleaning out dog cages, duties she volunteered for at a Brooklyn animal rescue centre to research her troubled waitress in Michaël Roskam’s riveting wintry crime-thriller The Drop. She spent weeks hanging round Copenhagen brothels and strip clubs to play a spiralling prostitute in Daisy Diamond, and endured multiple piercings and seven months of kickboxing to hone Salander’s prowling, feral presence for the Millennium series.

Never the type to delegate to stunt doubles for fear of chipping a nail, she also got her motorbike licence, racing a Honda at eye-watering speeds down frosty Swedish roads. The line between herself and her characters can get blurry, and whatever alchemy she tinkers with to get their blood running through her veins can bring unpredictable consequences. She remembers spending the wrap party of the Millennium films vomiting in the toilets, exorcising the angry cyber-hacker from her system, while her turn as a frail single mother in Pal Sletaune’s The Monitor, in which she seems to weigh only as much as a handful of feathers, gave her ghostly aches and pains that disappeared as mysteriously as they arrived when filming ended.

Coat by Lanvin, polo neck by Moncler, trousers by Paul Smith, necklace by Vionnet.

“I go in pyjamas to buy milk from the corner shop. In London you have all the madness of big parties, the creative buzz, the fashion, but you can disappear, too”

But none of that quite prepared her for What Happened to Monday, Tommy Wirkola’s dystopian new drama in which she stars opposite Willem Dafoe, Glenn Close – and herself. Or, more accurately, seven different versions of herself. The tale of septuplet sisters fighting for survival in a bleak Orwellian future, it was a schizophrenic jigsaw puzzle of a shoot, requiring green screens, impeccable timing and manic energy. On location in Bucharest, Rapace created an individual playlist, wardrobe and even perfume for each sister, digging to find nuances in their personalities that would resonate once they were let loose together onscreen. “I had to argue with myself, fight myself from different angles… On set I was dying in the morning and reacting to my own death in the afternoon – it was crazy,” she says. “I remember driving around here after the shoot and my short-term memory had gone. I had no idea where my house was! I turned down nine films after that – I was just destroyed.”

At one point during the filming, Rapace was hospitalised after a bad fall; the doctor recommended a three-week stay, but she was back on set three days later. “My body is becoming a map of scars,” she says with a laugh. “There’s one for every role – a broken foot, chemical scratches across my eyeball, stitches, a broken nose… ” (While playing a rogue CIA agent in Michael Apted’s Unlocked, she fractured her nose, passed out briefly, then carried on shooting.) Her action heroines are cut from the Ripley mould, out-muscling the guys without the sexy space-babe costumes. “I was a tomboy growing up, always training with the boys, doing martial arts, kung fu, boxing. I just never saw girls and boys differently,” she shrugs. “I still don’t.”

Shirt by Dries Van Noten, shoes by Dr Martens, brooch by Gillian Horsup at Grays Antiques.

“Everyone else was into the Spice Girls. I was into the Sex Pistols, The Clash, Blondie… I did my own piercings, wore fishnets and layers of military combat gear”

Rapace had a shifting, itinerant childhood: she was born in Hudiksvall on the snowy east coast of Sweden to a Swedish actor mother and Spanish flamenco-singer father. At the age of five she moved to a windswept Icelandic village, where her stepfather kept horses. Aged seven, it was a fleeting part in the bloodthirsty Viking epic In the Shadow of the Raven that planted her cinematic ambitions. “It changed my life. I was obsessed,” she says. When the family moved back to Sweden, eight-year-old Rapace was enrolled in a Rudolf Steiner school, “which isn’t posh in Sweden, it’s for the troubled kids”, she explains. “I was really wild. I always had a problem with authority and rules. I was very outspoken, stubborn, but also very creative.” By the time Rapace hit adolescence, she had styled herself as a mini-Nancy Spungen – at 14 she was peroxide blonde, living with an older guy, downing bottles of whisky and getting into bar fights at an age when her peers still had Disney characters printed on their duvets.

“I started drinking when I was really young. Everyone else was into the Spice Girls. I was into the Sex Pistols, The Clash, Blondie… I did my own piercings, wore fishnets and layers of military combat gear,” she remembers. But after a few lost days at Denmark’s sprawling Roskilde music festival she experienced something of an epiphany. “I thought, I’ve got to change,” she says. “I decided to go after my dream. So I left everyone, left that guy – who was not happy about it – moved to Stockholm alone and started working. I was 15.” Winning a place in drama school, she immediately started appearing on the Swedish soap Tre kronor. “It was watched by 3 million people every Wednesday. It was really big, but really bad. My character was in a girl-gang called Las Chicas,” she laughs. “By the time I was 18, I was living in an apartment with four girls, sleeping in the kitchen on a mattress, working in a bar and doing theatre at the same time. It was survival.”