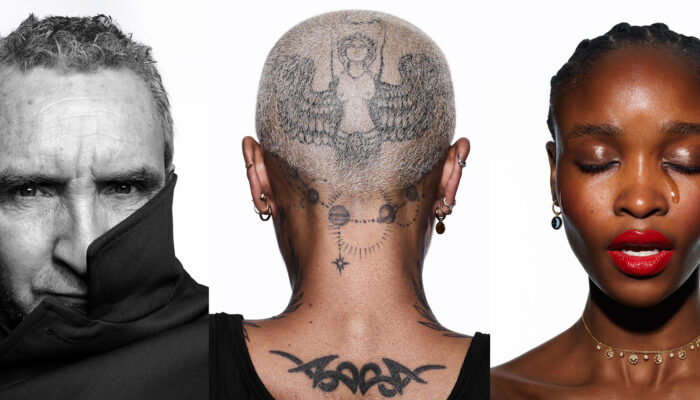

Araki, The Man

Photographed by Alex Lambrechts | Words by Hiromi Kitazawa | Translated by Kei Benger

Nobuyoshi Araki has pursued his extensive career as a photographer for more than 50 years, and as of last year, the total number of his published photobooks reached more than 500 volumes. He has held countless exhibitions both within Japan and internationally, yet 2017 could be described as an “Araki year”, with more solo exhibitions of his work taking place than ever before, providing anyone with an eye for these things the opportunity to chart the course of his artistic activities thus far and pinpoint what lies at the core of his photography, as well as his current state of mind.

Having been involved as curator for two large-scale exhibitions of Araki’s works held this last summer – ARAKI Nobuyoshi: Photo-Crazy A, at the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, and ARAKI Nobuyoshi: Sentimental Journey 1971-2017-, at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum – both of which featured more than 1,000 of his images, it feels as if, once again, we’re touching upon the greatness of his photography.

Araki initially began to develop an interest in photography thanks to the influence of his father, an amateur photographer. At university Araki studied photography and film, and for his graduation project produced Sachin, a series of films and photographs that captured children in an old quarter of downtown Tokyo, a place where Araki himself had spent his childhood. This project earned him the prestigious Taiyo award in 1964, marking his debut as a photographer. At the time, he was exploring various directions with his photography, creating scrapbooks, or “concept books”. One such valuable scrapbook, The Greengrocer (1964), was part of the Photo-Crazy A exhibition; it was the first time in 50 years that it had been on display and this early evidence of the artist’s ideas received much attention from the public.

The greengrocer himself – an old man whose stall was in the back alleys of Ginza, near the advertising agency where Araki worked as a commercial photographer at that time – had become a source of great fascination for Araki and he regularly photographed him. Having been heavily influenced by Italian neorealism since his days as a student, Araki began to regard the old man like a leading actor in Italian films. He took the self-printed gelatin silver prints and arranged them in different layouts on each page, bringing them together in a single book. More than 100 volumes of scrapbooks like this were produced, based on different themes and compositions; they became important studies that served as the cornerstone for the vast number of photobooks he subsequently came to publish.

Araki self-published the photobook Sentimental Journey following his marriage to his wife Yoko in 1971. “From then on, I began to focus and engage in shi-shashin – I-photographs,” he tells me. The Sentimental Journey 1971-2017- exhibition at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum was structured to trace Araki’s own sentimental journey that continues to this very day, from capturing Yoko, which could be considered the origins of Araki’s endeavours in shi-shashin, to the works that convey his feelings after Yoko’s death, and those created in recent years in which he appears to confront his own death. “At one point, I considered bringing my Sentimental Journey to an end with this exhibition,” Araki confesses. “Yet when I included the [dash] after the 2017 in the title, I got the idea that this was something that was going to continue forever, and indeed realised that ‘sentimental journey’ means my life with photography is still ongoing.”

In this manner, beginning with his father’s influence, those works in which he photographed children in an almost autobiographical manner for Sachin, his private life with Yoko, followed by her death, and more recently his confrontation with his own illness, are all aspects that concern Araki himself. The events born from the relationship between these aspects have had a profound effect on his photographic course. However, that’s not to say that, from time to time, it’s not possible to recognise glimpses of influences from creative minds such as Eugène Atget, Henri Cartier-Bresson or Andy Warhol, but Araki never studied under or lauded a specific photographer or artist.

“Old masters of the past eras, like the ukiyo-e painter Katsushika Hokusai and the nihonga painter Ito Jakuchu,” Araki offers when discussing any attempts at comparison. But rather than being influenced by their methods of expression per se, Araki appears to feel a resonance between himself and such painters in the sense that “we all possess the same spirit in pursuing our own paths”. Since entering his seventies, Araki has referred to himself as Shakyo Rojin (Photo-Mad Old Man) in an homage to Hokusai, who in his mid-seventies adopted the pseudonym Gakyo Rojin Manji (Old Man Crazy About Painting). Harboured within this name is Araki’s personal nudge of encouragement to himself, inspired by Hokusai’s claim to have only been able to paint the way he wanted to after entering his seventies. Araki explains: “I found myself finally able to take photographs after I reached 70. Or rather, I got to a stage of being granted the blessing of taking photographs, and therefore I’m now able to sense the real truth that permeates photography.”

As if testament to this, in his latest works, One Hundred Views of the Sky and One Hundred Views of Flowers, the sense of life and death (a significant and constant theme throughout his works) emerges in an unprecedented way. Araki’s previous photographs were often viewed through the proverbial lens of colour representing life and monochrome representing death, yet it’s easy to see now that it’s not simply a matter of life or death. It’s evident that he has now arrived at a place in which those two disparate states begin to coalesce with one another – in a sense, even conveying life within death, or life and death in a much larger context that encompasses the cycle of life itself.

This is an extract of an article taken from the latest issue of THE FALL available to purchase from nationwide retailers and our Shopify store here.